July 17, 2019

Mental Health

In my work as a consultant helping young scholars navigate the demands of academic life, one of the most common fears expressed by my clients is that they don’t belong. For them, every paper submitted or experiment conducted carries not only the stress of the task, but also the threat of being revealed as a fraud. This is the burden of “The Imposter Syndrome,” a term first coined in 1978 by psychologists Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes.

The fact that this phenomenon is so prevalent as to warrant its own label should be comforting. If feeling like an imposter makes you just like a bunch of other people in your field, then by definition, you belong. Yet like many scholars, you might remain unconvinced and develop a sort of meta-imposter syndrome, in which you think your colleagues all have the “Imposter Syndrome,” while you alone are actually an imposter.

Source: https://goo.gl/E4Qnc5

So how can you know for sure if you really belong? Let’s look at some common concerns and see if they mean you’re an imposter. First, what if you’re pretty bad at some important aspect of your job? Does this glaring weakness mean that you’re not cut out for your field? In short, no. Everyone has weaknesses, and you’re not an imposter. In fact, experts in any field spend the majority of their practice time working on their weaknesses. That’s why they’re experts: because they recognize what they’re not good at and work to get better. So if you know what you need to improve, you’re in good company.

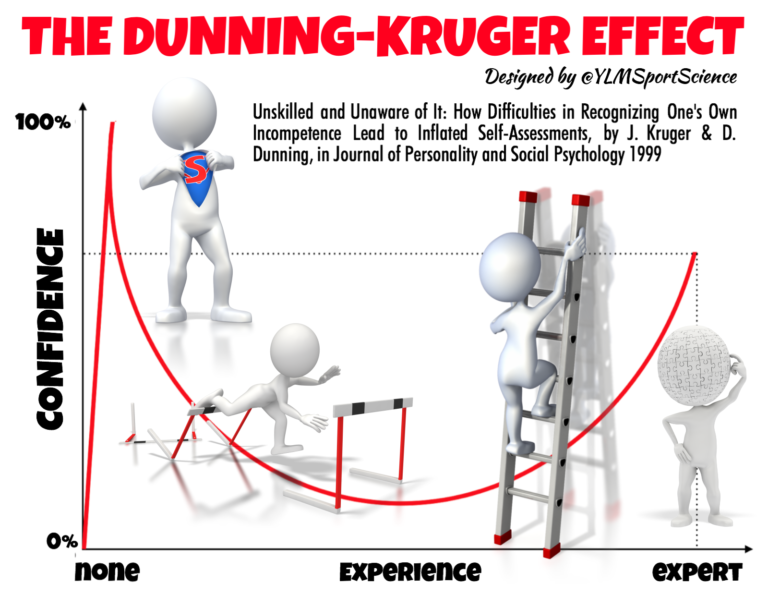

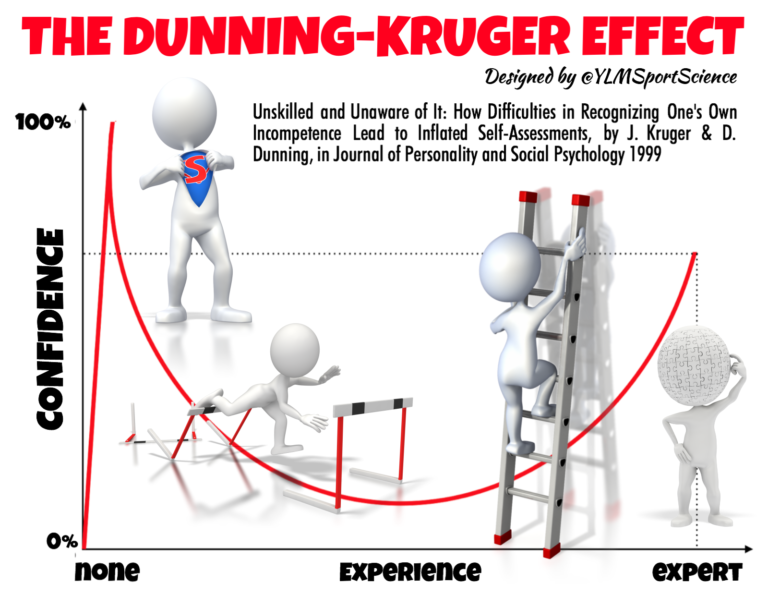

But what if you don’t have any weaknesses? If that describes you, I’d be surprised, because I wouldn’t have expected you to click on this post. But if you’re reading this and are now worried that you’re an imposter because you’re the only one without any shortcomings, you can rest assured. You have stuff to work on, like the rest of us, but you’re not an imposter. You’re simply blind to the weaknesses you have, and there are plenty of people around just like you. There’s even a name for your syndrome as well. It’s the “Dunning-Kruger Effect.” Look it up.

Source: https://goo.gl/xt8qKd

What, though, if your concern is that you’re all weaknesses and no strengths? Does that mean you’re an imposter? No again. Clearly, if you’ve reached some level of achievement, you have leveraged some strengths to do so, and if you believe otherwise, it’s because you’re blind to your strengths, or you’re extremely humble. Like many “Imposter Syndrome” sufferers, you probably ruminate on your weaknesses while taking your strengths for granted.

It’s true. There are things you can do, without even thinking about it, that others find quite challenging. Still, you may discount your strengths because you had to put in extra effort to get good at them. You may think you’re an imposter because nothing comes easy for you. Yet that doesn’t make you an imposter, either. For one, if you have a habit of working hard, that’s a valuable strength in itself. Also, another proven quality of experts is that they spend more time than others practicing on their own, so if you have to work hard to accomplish something, you’re not an imposter. More likely, you’re an emerging expert.

For many scholars, the fear of not belonging is tied to identity. If you’re a member of a group that has been traditionally under-represented in your field, you may feel the burden of disproving negative stereotypes about your gender, race, culture, or other intersecting identities, a phenomenon known as “Stereotype Threat.” Let me assure you, if you’ve overcome discrimination and biased perceptions, either explicit or implicit, to get to where you are, you darn well deserve to be there. You are definitely not an imposter.

Source: https://goo.gl/xiJpfw

When it comes down to it, there is only one true test to know if you’re an imposter. To take it, find your ID card, for whichever organization within which you reside. Is that your real name on the card? Is that your photograph? If not, and you’ve falsified your credentials, then you are an imposter, and I hope you get caught. If, however, that is your actual name on your ID, then you’re not an imposter. Rather, you’re a card-carrying member, with all the honors, rights, and privileges thereunto appertaining. So go ahead and ask that question you’ve been wondering about at the conference seminar. And send that message to that prestigious potential collaborator. You deserve to be here, so use your voice. I, for one, look forward to hearing from you.

This blog is re-published with permission from the author, David Sacks, PhD. It was originally published in 2018 on EdgeForScholars.org